What's in this article?

- 1 Barrett’s Esophagus Overview

- 2 Causes and Risk Factors of Barrett’s Esophagus

- 3 Does GERD Always Cause Barrett’s Esophagus?

- 4 Symptoms of Barrett’s Esophagus

- 5 How Does GERD Relate to Barrett’s Esophagus?

- 6 Many people with Barrett’s Esophagus have no signs or symptoms.

- 7 How is Barrett’s Esophagus Diagnosed?

- 8 Treatment Options for Barrett’s Esophagus

Barrett’s Esophagus Overview

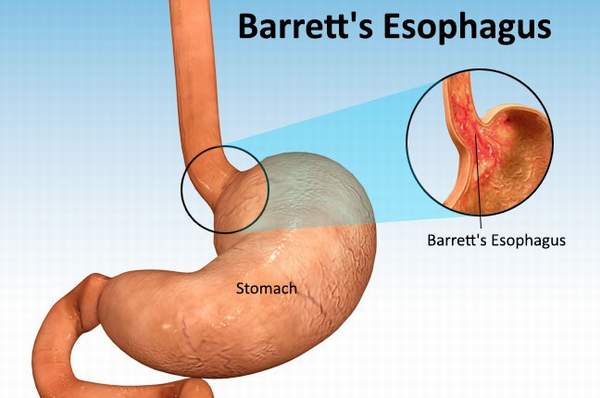

In Barrett’s esophagus, tissue in the tube connecting your mouth and stomach (esophagus) is replaced by tissue similar to the intestinal lining.

Barrett’s esophagus is most often diagnosed in people who have long-term gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) a chronic regurgitation of acid from the stomach into the lower esophagus. Only a small percentage of people with GERD will develop Barrett’s esophagus.

Barrett’s esophagus is associated with an increased risk of developing esophageal cancer. Although the risk is small, it’s important to have regular checkups for precancerous cells. If precancerous cells are discovered, they can be treated to prevent esophageal cancer.

Causes and Risk Factors of Barrett’s Esophagus

The exact cause of Barrett’s esophagus is not yet known, but the condition is most commonly seen in those with some sort of reflux like GER. GER occurs when the muscles at the bottom of the esophagus that are supposed to close and prevent food and acid from coming back up into the esophagus do not work properly. It is believed that cells of the esophagus can become abnormal when trying to heal from repeated exposure to the stomach acid. Though GER is often seen in those with Barrett’s esophagus, it is entirely possible for you to have Barrett’s esophagus and not have any sort of reflux or heartburn.

If you have heartburn or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) for longer than 10 years, you have an increased risk of developing Barrett’s esophagus because of the damage that stomach acid causes to the esophagus. The condition is more common in men than women, and white people are at higher risk of developing Barrett’s esophagus than others. Though Barrett’s esophagus can occur at any age, it is more common in those over the age of 50.

Does GERD Always Cause Barrett’s Esophagus?

No. Not everyone with GERD develops Barrett’s esophagus. And not everyone with Barrett’s esophagus had GERD. But long-term GERD is the primary risk factor.

Anyone can develop Barrett’s esophagus, but white males who have had long-term GERD are more likely than others to develop it. Other risk factors include the onset of GERD at a younger age and a history of current or past smoking.

Symptoms of Barrett’s Esophagus

The tissue changes that characterize Barrett’s esophagus cause no symptoms. The signs and symptoms that you experience are generally due to GERD and may include:

- Frequent heartburn

- Difficulty swallowing food

- Less commonly, chest pain

How Does GERD Relate to Barrett’s Esophagus?

People with GERD may experience symptoms such as heartburn, a sour, burning sensation in the back of the throat, chronic cough, laryngitis, and nausea.

When you swallow food or liquid, it automatically passes through the esophagus, which is a hollow, muscular tube that runs from your throat to your stomach. The lower esophageal sphincter, a ring of muscle at the end of the esophagus where it joins the stomach, keeps stomach contents from rising up into the esophagus.

The stomach produces acid in order to digest food, but it is also protected from the acid it produces. With GERD, stomach contents flow backward into the esophagus. This is known as reflux.

Most people with acid reflux don’t develop Barrett’s esophagus. But in patients with frequent acid reflux, the normal cells in the esophagus may eventually be replaced by cells that are similar to cells in the intestine to become Barrett’s esophagus.

Many people with Barrett’s Esophagus have no signs or symptoms.

Barrett’s esophagus itself does not have any symptoms and most of the symptoms that you may experience are related to the acid reflux that sometimes occurs. Some symptoms of acid reflux are pain in the chest and abdomen as well as a dry cough. You may also experience difficulty with swallowing and frequent heartburn. If you vomit blood, you should seek immediate medical attention. Vomited blood may be red or look like coffee grounds, and if you experience bloody or tar-like stools, consult with your physician as soon as you can.

How is Barrett’s Esophagus Diagnosed?

Because there are often no specific symptoms associated with Barrett’s esophagus, it can only be diagnosed with an upper endoscopy and biopsy. Guidelines from the American Gastroenterological Association recommend screening in people who have multiple risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus. Risk factors include age over 50, male sex, white race, hiatal hernia, long standing GERD, and overweight, especially if weight is carried around the middle.

To perform an endoscopy, a doctor called a gastroenterologist inserts a long flexible tube with a camera attached down the throat into the esophagus after giving the patient a sedative. The process may feel a little uncomfortable, but it isn’t painful. Most people have little or no problem with it.

Once the tube is inserted, the doctor can visually inspect the lining of the esophagus. Barrett’s esophagus, if it’s there, is visible on camera, but the diagnosis requires a biopsy. The doctor will remove a small sample of tissue to be examined under a microscope in the laboratory to confirm a diagnosis.

The sample will also be examined for the presence of precancerous cells or cancer. If the biopsy confirms the presence of Barrett’s esophagus, your doctor will probably recommend a follow-up endoscopy and biopsy to examine more tissue for early signs of developing cancer.

If you have Barrett’s esophagus but no cancer or precancerous cells are found, the doctor will still most likely recommend that you have periodic repeat endoscopy. This is a precaution, because cancer can develop in Barrett tissue years after diagnosing Barrett’s esophagus. If precancerous cells are present in the biopsy, your doctor will discuss treatment and surveillance options with you.

Treatment Options for Barrett’s Esophagus

Treatment for Barrett’s esophagus depends on what level of dysplasia your doctor determines you have.

No or Low-Grade Dysplasia

Those with no or low-grade dysplasia are usually treated by treating the GER or GERD that is associated with Barrett’s esophagus. Medications are often prescribed to help with the symptoms that GER and GERD cause. In some cases, surgery is performed on the sphincter located at the bottom of the esophagus to help keep acid from backing up into the esophagus. While medication and surgery will help with GER symptoms and continued damage, it is not a cure for Barrett’s esophagus. If you have low or no dysplasia, your doctor will likely schedule you for yearly endoscopy procedures to make sure that your condition has not advanced.

High Grade Displasia

If you have high-grade dysplasia, your doctor may want to employ the use of more invasive procedures to remove the affected area of your esophagus. Your doctor may remove damaged areas of the esophagus through the use of endoscopy. In some cases, removal of an entire portion of the esophagus may be performed, though it is typically not recommended due to the complications that may arise. An experienced surgeon would reduce the risk of complications, but you still may experience bleeding or narrowing of the esophagus after surgery.

Radiofrequency ablation is a method of using heat to destroy damaged esophageal tissue through the use of bursts of energy. A similar method called cryotherapy, which involves the use of a cold liquid or gas to freeze the abnormal cells, is also sometimes used. After the cells thaw out, they are frozen again, and this process is repeated until the cells inevitably die from the damage caused by the repeated freezing and thawing. Both of these methods of treatment can result in chest pain and narrowing of the esophagus.

With treatment methods other than the removal of the esophagus, Barrett’s esophagus can return. Doctors often recommend regular endoscopies.

hi!,I love your writing so so much! share we keep in touch more approximately your article on AOL?

I need an expert in this area to resolve my problem.

Maybe that is you! Taking a look ahead to peer you.

Very nice write-up. I certainly love this site. Continue the good work!